“LE CHÂTEAU DE MA MÈRE” - THE BACKGROUND TO THE BOOK

INTRODUCTION

- The timespan of the book

Pagnol’s novel gives us a vivid picture of life in France in the first decade of the 20th century. The story begins in the summer of 1904, when the family are on holiday in a rented holiday villa. The main action of this piece of his autobiography ends in the following year, when the family are beginning their summer vacation once again at the same house.

- The Geographical setting of the book

Photo above - the path that Marcel and Lili used to take.

Marcel's father, Joseph, was an instituteur in a school in Marseille where they had their home, but he and his family liked to escape from the big city to live amidst nature in the wild countryside nearby. Most of this novel concentrates on their stays there in these fourteen or so months.

Their country home, La Bastide Neuve (meaning, in theory “new country house” but, in fact, not new at all), - is in a district called Les Bellons next to the quiet Provençal village of village of La Treille. They are approximately ten miles from Marseille and only a few miles from the town of Aubagne where the Pagnol family had been living when Marcel was born. The house is in a hilly area of pasture and forest, on the edge of the belt of wild scrubland that runs as far as Aix. The French word for this is “garrigue”, consisting of soft-leaved scrub that can survive the parched summers.

Five mountain peaks dominate the skyline : La tête Rouge, the Peak of Taoumé, the Puits du Tubé, the Plan de l’Aigle and most spectacularly Mount Garbalin, an outcrop of white limestone forming a massive block, which was a landmark for ships passing along the Mediterranean coast -(See the map on the index page).

On the first page of the novel, Pagnol describes this dramatic backdrop as Marcel, at the age of nine, sets out, on a hunting trip, with his father, and his Uncle Jules:

Sur les barres du plan de l’Aigle, le bord de la nuit amincie était brodé de brumes blanches………… Là, sur la longue plaine qui montait vers le Taoumé, les rayons rouges du soleil nouveau faisaient peu à peu surgir les pins, les cades (juniper), les messugues (rock roses) et comme un navire qui sort de la brume, la haute proue du pic solitaire se dressait soudain devant nous.

The major part of the story of « Le château de ma mère » is the account of the times that the family spent at this retreat in the hills of Provence, where the climate suited Mme Pagnol’s somewhat frail constitution. From the Easter period of the following year, their visits to the holiday home became even more frequent, as they made the journey to the Bastide Neuve every weekend. This had been made possible by the revision of M. Pagnol’s teaching timetable, which gave him Monday mornings free for the return journey - an arrangement achieved by Mme Augustine Pagnol’s secret initiative with the headmaster's wife.

.

SECTION A -Aspects of country life in France at the start of the 20th Century

A1) -The centuries old lifestyle

In view of its largely rustic setting, the book gives us a picture of the lives of the country people of Provence at the start of the 20th century. In many ways this must have changed very little over the centuries. When we are told at the start of the book, that their peasant friend, François, sometimes used to sleep in the ancient sheep pen on the plain leading up to the Taoumé, we think of shepherds right back to ancient times, sleeping with their flocks. This was the primitive lifestyle to which Marcel's younger brother, Paul, in his adult years would escape to,in order to avoid the pressures of the later 20th century:

Page 168- …. …..il menait son troupeau de chèvres ; le soir, il faisait des fromages dans des tamis de joncs tressés, puis sur le gravier des garrigues, il dormait, roulé dans son grand manteau : Il fut le dernier chevrier de Virgile.It is from Marcel's close friendship with the peasant boy, Lili, that he gets to know about the ideas and habits of the local people. The description of Lili draws attention to his peasant stock

Page 20:

"Il était brun, avec un fin visage provençal, des yeux noirs, de longs cils de fille. Il portait, sous un vieux gilet de laine grise, une chemise brune à manches longues qu'il avait roulées jusqu au-dessus des coudes, une culotte courte, et des espadrilles de corde comme les miennes, mais il n'avait pas de chaussettes."Although Lili was restrained and polite in the Pagnol home, alone with Marcel he was capable of using the crude expressions of the peasant- Page 38. One morning the hunting party set off under threatening skies, but Uncle Jules assured them that it would not rain. At this, Lili, who knew how to read the warning signs much better winked and make a rude remark he had got from his big brother. He said that if Uncle Jules had to drink all the rain that was going to fall, he would still be pissing at Christmas:

"S'il fallait qu'il boive tout ce qui va tomber, il pisserait jusqu’à la Noel. »A distinct feature of the personal habits of the peasants emerges when Marcel makes as his excuse for not staying on the mountain the necessity for a townsperson like him to wash every day. Lili tells him that he only washed on Sundays like everyone else. In fact some washed much less regularly than that. The old poacher, Edmond de Parpaillouns has never had a wash in his life and he has turned seventy and look how fit he looks.

A2) -The character of the country people

a) The peasants’ protectiveness of their lands

The peasants regarded the land where they lived as theirs by right whatever legal documents might say. When Uncle Jules teasingly admonished him for poaching, Lili said that he came from Les Bellons and a peasant cannot be a poacher on the hills of his home .

Ça veut dire que ces collines c'est le bien des gens d'ici. Ça fait qu'on n'est pas des braconniers.The local people were wary of the intrusion of outsiders into their lives. They regarded the townspeople who came as day trippers trip as the main enemies – once after a row with the locals, some of them had retaliated by relieving themselves in a spring of drinking water – sacrilege to the peasant!

Lili tells them how jealously the local people protect their domains. A neighbour of his, Chabert, had fired a gun to scare off the day trippers. When Marcel expressed surprise, Lili explained that Chabert had only fired at long range with small shot and that they were stealing cherries from the one and only cherry tree he possessed. His father, François, had said that Chabert should have fired buck shot. Uncle Jules commented that this was a bit uncivilized and this made Lili very indignant. Hequotes how two years ago visitors had lit a fire among a plantation of new pines to cook their steaks, which he finds incredible - Page 28.

One secret that the peasants kept to themselves in that desperately dry region was the location of the springs of water in the hills. When M. Pagnol asked Lili where spring of water could be found he replied he was forbidden to tell. In fact, their locations were kept secret by the peasants even from their own families. Lili's grandfather had known a secret mountain spring - and had tried to pass its whereabouts on to his son on his deathbed, but he had died before he could finish the sentence - the spring was lost forever!

b) The independence of the peasantry

We form the impression that the peasantry was a proud, independent folk and to some extent a law unto themselves. When Marcel told Lili about their bad experience with the terrifying gamekeeper in the last château, he showed a peasant’s distrust of the authorities - Page 154 Above all, Lili was upset to hear that the gamekeeper had written a summons in his book:

Le procès-verbal, pour les gens de mon village, c'était le déshonneur et la ruine. Un gendarme d'Aubagne avait été tué dans la colline, par un brave homme de paysan, parce qu'il allait lui faire un procès-verbal.Lili went on to make enquiries about the aggressive gamekeeper and found out that he was had already earned a bad reputation locally P 158. He had already got a local peasant fined for poaching and Lili added in a matter of fact way that the gamekeeper would be shot dead if he came into the mountains! – However, it has to be said that Lili did use exaggeration at times. When Lili was trying to persuade Marcel’s mother that, even if M. Pagnol was unemployed, they could still live off the land, he got carried away on describing the fecundity Lili of the chick-pea and the haricot. He said that the bean was so quick-growing that you put the seed in the ground and ran away. Then, looking at mother, he said:

- Naturellement, c'est un peu exagéré: mais c'est pour dire qu'il pousse vitec) The superstitions of the peasantry

The peasants hrld on to their old superstitious beliefs. When Marcel is accompanied by Lili into the hills on his night escapade, he is frightened by a passing shadow. Lili immediately assumes that it is the ghost of a Shepherd of long ago who was murdered for his money and who returns to the mountains in search. As Marcel is planning to live alone on the mountain like a hermit, he does not wish to believe in the apparition. Lili, however, is absolutely certain, because his father had seen it on four occasions. Lili tells how, on its last visit, his father had dealt with it in a very resolute manner Page 74. His father had told the ghost that he hadn't got his money, and that if he didn't clear off he'd give him the signs of the cross and six kicks up the backside

"Moi, je respecte les morts, mais si tu continues comme ça moi je sors, et je te fous quatre signes de croix et six coups de pied au derrière".d) The kindness and helpfulness of the local people

The Pagnols were left with a deep impression of the kindness of these people because of the lengths they went to, in order to help his family. The 40-year-old servant at the second big house, Dominique, had come rushing towards them, brandishing his garden fork. It had seemed at first that he was chasing them off. In fact, at the same time, he was signalling to them that he was putting on the display for the sake of his employer, who was watching from a top window.

The pantomime that he performed, to deceive his master, was most imaginative. On parting, Dominique advised them how to cross the estate, in future, without being seen. His further acts of kindness were to leave out for them each Saturday gifts of fruit and vegetables. M. Pagnol paid tribute to the qualities of the peasantry, in words which are unfortunately rather superior and patronising. Page 134:

" Tel est le peuple : ses défauts ne viennent que de son ignorance. Mais son cœur est bon comme le bon pain »e) The so-called « ignorance » of the peasantry.

In spite of all his love for the Lili, Marcel’s attitude to him seemed to show an unquestioned acceptance of his father’s view of the “ignorance” of the peasantry. He tells us P 33:

"D'autre part, j'avais constaté que dans son ignorance, il me considérait comme un savant: je m'efforçai de justifier cette opinion. »Marcel showed off shamefully and taught Lili the 13 times table and the longest words possible:

"Mon but n'était pas d'augmenter son vocabulaire, mais son admiration, qui s'allongeait avec les mots.However, Marcel later realised the unacceptability of his behaviour, when he was tempted to be superior about the letter he received from Lili which was full of mistakes and ink blots. After the first drafting a letter with sardonic comment, he destroyed it and wrote a new letter of a friend in which Marcel deliberately made spelling mistakes and adorned his own page with ink blots.

M. Pagnol’s sweeping reference to the ignorance of the common people requires qualification. We know that François, their peasant neighbour, could not read, because Lili bluntly reminded Lili of the fact on the night that he ran away from home. Marcel needed to make this point to discredit Lili’s father’s story of a ghost, who haunted the mountains. Marcel wanted to believe that François only believed in ghosts because he was uneducated. Lili with his peasant humility does not take offence but he stands his ground and gives Marcel relevant facts in reply. In fact the new generation of peasant children were receiving an education and Lili at the age of eight had the confidence to write down his thoughts in a letter to his friend.

We feel that the author is conveying his view of the silliness of these overtones of intellectual arrogance. Pagnol also laughs at the emptiness of some parts of the contemporary academic syllabus, which was widely regarded as the sole route to success and wealth.he tells how

Marcel’s preparation for his scholarship exam required him to be able to recite by heart the names of all the sub-prefectures of France.Lili’s cleverness and knowledge was of a different composition. He had a remarkably detailed knowledge of the area in which he lived that greatly impressed Marcel and his family. He knew all the plants, where they were found, the weather, the different features of the landscape:

Lili savait tout; le temps qu’il ferait, les sources cachées, les ravins où l’on trouve des champignons, des salades sauvages, des pins amandiers, des prunelles, des arbousiers.

He had many skills and was remarkable for his resourcefulness. After Marcel had boastfully claimed that he would make a spear to kill the great Owls, it was Lili who went immediately into the thicket to choose a suitable juniper stick, which he quickly sharpened to a pencil sharp point with his knife Page 77. Marcel was amazed by Lili’s intricate skills in baiting his traps- Page 21.

(f) The status of the peasantry in contemporary society

Lili was conscious that he came from an inferior social class and when he was invited to join the Christmas Eve dinner at the Pagnol's, he tried to imitate the manners of Marcel:

Lili, notre invité d'honneur - observa tous mes gestes et s'efforça d'imiter le gentleman qu'il croyait que j’étais.

He was hypnotised by what to him was the wealth of all the presents hanging on the Pagnol’s Christmas tree.Marcel was aware of the wonderment, with which Lili was filled when he described to him the richness and the splendour of the big city of Marseille, with its well-stocked shops. Lili just enjoyed these stories and joined in with Marcel, imitating with him the screams of the female passengers on the thrilling rides in the Marseille pleasure Park “Magic city”.

The Pagnols appear to take for granted the status of these two classes of society, while resenting the top status assumed by the nobility. For example when the Pagnols are taking their seats on the bus at the end of their holiday, the other members of the family did not want to sit on the empty rear-facing back seat, and were forced to sit in the middle of the bus, among the peasants Page 85:

La dernière banquette, qui tourne le dos aux chevaux, était vide: comme ma mère et Paul avaient des nausées quand on les transportait à reculons, la famille s’installa au milieu des paysans, tandis que j’allais m’asseoir à l’arrière tout seul.Despite their patronising lapses, the Pagnol family had a great love of the local people and a great admiration for their skills. They appreciated their help and kindness and whatever the social difference, they treated Lili as a member of their family. This became embarrassing for Lili on the day when the two boys returned cold and soaked after their adventures in the dramatic thunder storm. Mme Pagnol stripped him and rubbed him down as she did her own son and this went against Lili’s peasant modesty.

Pagnol paints a very warm picture of this unpretentious little boy of great common sense, who immediately became - and remained ever after- his very loyal friend. On the bleak page of the penultimate chapter, he lists, in the three devastating tragedies of these years, the death of this close friend from a peasant family in La Treille killed by a bullet through the head in the final stages of World War One.

Marcel’s brother, Paul, severely disabled by epilepsy, made a strong statement of his admiration for these country people and their lifestyle when he turned his back on middle class life and spent the rest of his curtailed life, leading the life of a goatherd, sleeping with his flock on these hills, just as Lili’s father, François, was accustomed to do in those years when the Pagnol family spent their holidays nearby at Les Bellons.

SECTION B The general picture French life at the start of the 20th Century

Although the book is set mainly in a rural environment, the Pagnols are a lower middle-class family and through their lives and their ideas we also have more general picture of life in France at this point in history.

B1) –Aspects of their daily life

a) The pre- dawn of the great technological revolution of the 20th century 1904- 1905

At the start of the 20th century, the industrial revolution was already over 100 years old and important technological advances had been made. On the Pagnol's journey to their country home, we see two of these illustrated: steam power and electricity. Previously the trams running in Marseille were steam driven, but now they were powered by electricity:

….. un tram à vapeur, qui, sous une cheminée en entonnoir, avait été, comme toute chose, le dernier mot du progrès. Mais le Progrès ne cesse jamais de parler et il avait dit un autre dernier mot, qui était : "le tram électrique".In spite of these few modern developments, the way of life of the people had not dramatically changed from that of previous centuries. Marcel Pagnol, as a leading figure in the French film industry, liked reminding people that, in 1895, the year of his birth, the Lumière brothers, were only a few miles from his birthplace of Aubagne, when they made their first public demonstration of moving pictures, with shots of a train arriving in the station of La Ciotat. During Pagnol’s youth and early adult life, cinematography, like many of the major technologies of the 20th century was still in its very earliest stage of development and this was merely the pre-dawn of the revolutionary transformations to come. The novel, therefore mainly affords us a look at a disappearing world.

b) Changing transport options

M. Pagnol an amusing story about the problem of introducing new technology. The city of Marseille had decided to remove a long detour on their tram track by cutting a tunnel through a big hill in the suburbs. M. Pagnol describes how two teams of navvies began to dig from the opposite sides of the hill to be pierced. Although the distance to cross was 300 yards, the teams continually lost their way and had difficulty in meeting up. As a result the tunnel route finished up with so many twists and turns that passengers ended with a long and swerving journey underground :

Page 98: Mon père nous expliqua que cet ouvrage singulier avait été commencé par les deux bouts, mais que les équipes terrassières, après une longue et sinueuse flânerie souterraine, ne s'étaient rencontrées que par hasard"Road travel

In 1904,the year our story begins, was the year when the first petrol powered buses made their appearance in big cities such as London, offering new competition with the trams. Nevertheless, for the majority of people, bus travel, at this period, meant horse drawn carriages At the end of their first holiday at the Bastide Neuve, the Pagnols are able to hire Francois’s cart to take them from the villa to la Treille, where on Sundays, they could catch a horse drawn bus to the tram stop at La Barasse. Pagnol paints a vivid picture -Page 84- of the departure of the Sunday bus pulled by two horses:

C’était une longue voiture verte, et de son toit pendaient des courts rideaux de toile, ornés d’une frange de ficelle. Les deux chevaux piaffaient (stamping their hoofs) , et le cocher , sous une pèlerine grise et un chapeau de toile cirée, sonnaient de l’oliphant(post-horn) pour appeler les retardataires.Carthorses were used for other heavy duties such as home removals. When the Pagnols, overladen with luggage, were making the long walk to their first Christmas at their cottage, it was a passing carter, who took pity on Marcel’s mother. His cart was fully loaded but, without a word, he took her bags from her and hung them underneath his cart.

This first decade had seen the early development of the internal combustion engine. Bouzigue makes the motor car his symbol for speed of travel, when he tells Marcel's family than his key would take them along the canal pathway more quickly than a motorcar - Marcel is doubtful, having seen the wonder of the new Panhard model in a recent advertisement: “La voiture qui a fait le kilomètre en une minute”. In these years, however, the motor car would have been a rare sight, even in the big towns

c) The limitations of medical and scientific knowledge at this time.

(i) In the early 1900s, when modern medicines and treatments were not available,death could strike at any age. In these years before the discovery of anti-biotics, even illnesses like scarlet fever were very often fatal. The terrible epidemics that struck Europe in the first decades of the 20th century had mortality rates as high as those of the First World War. We can understand Mme. Pagnol's anxiety that her son should not go out in the teeming autumn rain to clear the traps with Lili. She feared that this put him at risk of catching pneumonia, which was commonly fatal in those days: PAGE 59

(ii) The effect of Phylloxera on the French vineyards and the French economy

The great French wine blight, phylloxera, had catastrophically reduced the French vine harvests from the late 1850s onwards and had threatened the French economy. Recovery from it had been slow.

On Page 32 we are told that Lili knew where there was a vine that had survived the phylloxera.

..il connaissait au fond d'un hallier, quelques pieds de vigne qui avaient échappé au phylloxéra et qui mûrissaient dans la solitude des grappes aigrelettes mais délicieuses.Modern science has controlled phylloxera but not eliminated it. In the context of the earlier section on the superstition of the peasantry, I was interested to read, in a history document, that when the peasants were seeing all their crops wiped out by the disease in the 19th century, some of them, in the depths of despair, turned to their ancient religion, and used protective rituals from pre-Christian times.

d) LOCAL COLOUR

(i) The picture of the traditional Christmas meal in Provence

Spending Christmas at their villa in the country, the Pagnols have prepared the big Christmas meal traditional in Provence. This takes place in the early hours of Christmas Day. For practising Catholics, like Uncle Jules, this means on return from Midnight Mass.

There is a crackling fire, which had been lit in the brazier that very evening to roast the meats. These included grilled thrush, birds that the boys had trapped. With a little joke that probably makes some English readers uneasy, Marcel makes a pun that the thrushes had fallen from “branche en broche.”

The meal is called "le grand souper des treize desserts", because, according to the local custom, thirteen varieties of dessert were eaten: oranges, dates, nuts, raisins etc. and the children, although tired, stayed up into the early hours, enjoying all these treats.(ii) An amusing detail of contemporary habits - Queuing techniques in 1904

There is an amusing description of queuing techniques at the tram station in Marseille. There was long queue waiting contained between metal barriers. The queue didn't grow any longer as more and more people came - only more compressed.

"une longue file que les nouveaux arrivants n'allongeaient pas, mais comprimaient".When the tram arrived, and the gate to the track was opened, the Pagnols were carried forward by the surge and Marcel’s mother found herself swept into a good seat by two stout ladies p 98.

Un employé à casquette ouvrit le portillon, et la ruée nous emporta.

Ma mère, mue par deux magnifiques commères, se trouva assise en bonne place sans avoir rien fait pour le mériter.A note of my own personal nostalgia- when I was at a French university more than half a century later, I had exactly the same experience in the lunch queues, where the students joining at the back sought to move forward by pushing. As my direct neighbours in the crush, against whom I was progressively compressed, almost to the point of suffocation, were very often attractive female students, I was not unappreciative of this old tradition.

B2) – Aspects of French political life in the first decade of the twentieth century

a) A contemporary political figure to fix the date

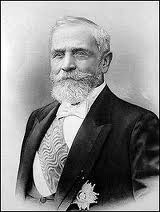

The year that the book starts is 1904 and the gentleman who looks down upon them with a faint smile from the portrait on the wall of their country retreat -- Page 66 -- is Armand Fallières,(see above), a southern French politician, who was then President of the Senate and was, shortly afterwards, elected President of France (1906 -- 1913).

b) The bitter memory of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870

On July 19, 1870, France under the Emperor Napoleon III had declared war on Prussia on account of a series of disputes with the powerful Prussian Chancellor, Bismark. In fact, France was insufficiently prepared for war and the Prussian army, joined by the other German states had superior numbers and weaponry. A series of French military reverses followed, culminating in a crushing defeat at Sedan on September 1st 1870 when after a nine hour battle, the Emperor surrendered to prevent further pointless casualties in a hopeless situation. The war was ended by the Treaty of Frankfurt, signed on May 10, 1871, between France and Germany. The treaty provided for the French province of Alsace (excepting Belfort) and part of Lorraine, including Metz, to be handed over to the German Empire.

We see in this book that the bitterness of this debacle continued to rankle in France, whose armies under Napoleon Bonaparte, at the start of the century, had won glorious victories. We see the depth of feeling even in a mild man like Joseph Pagnol by his reaction to Bouzigue’s mention of the political passions of the family of peasants that look after the third château. Bouzigue says that the deaf grandfather is always talking about the war of 1870 and wants to recapture Alsace –Lorraine. Marcel’s father totally approves of his attitude and says he is a good Frenchman

Il me parle toujours de la guerre de septante, et il veut reprendre l'Alsace-Lorraine.

"C'est un bon Français", dit mon père.This war is recalled again in a later incident in the story: One Saturday in May 1905, the Pagnol family was passing through the grounds of the first château when they came face-to-face with the owner. He was very tall and had a white beard and on one side of his face was a big scar, stretching to the eye socket, from which the eye was missing.

When he approaches, Marcel’s little sister is frightened by the scar and tells the old man that he is too ugly. The latter apologises for his thoughtlessness over his appearance and explains to Marcel’s mother that the wound had been caused by a German lance in a hop-field in Alsace nearly 35 years ago (ie the war of 1870). He suggests she should tell the little girl that a cat scratched him, so that she will always be careful with them from then on.

….j’oublie facilement ce cette balafre: ce fut le dernier coup de lance d’un uhlan, dans une houblonnière en Alsace, il y a près de trente-cinq ans. Page 130On leaving them, the Count gives them his card. That evening, at la Bastide Neuve, the parents read his card and see that the old Count had been Colonel of the First Cuirassier. At this, Marcel’s mother hesitated, as if she was troubled and said “So then….” But her husband finished her sentence for her to confirm that it was the First Cuirassier that had been at the battle of Reichshoffen – At this battle in August 1870, Le Premier Cuirassier, an elite cavalry brigade, had made heroic but futile cavalry charges against a Prussian army that outnumbered them three to one. They had become legendary for their bravery and sacrifice in the face of the superior firepower.

One day Marcel’s father showed the Count an old book he had unearthed, in which there was an account of the battle of Reichshoffen with the Colonel's name very prominent. My father had meticulously drawn the French tricolour around the pages recounting their valour, even though he thought himself anti-militarist –

…. mon père qui se croyait antimilitariste, avait longuement taillé trois crayons, pour entourer d'un cadre tricolore les pages où l'auteur célébrait la vaillance du "Premier Cuirassier" P 132.The Colonel did not accept this as a true account and at once set about writing his own version. Perhaps we can assume that he had no time for the romanticizing of a day of which he had narrowly survived the real horror.

(c ) The view the book gives of the new French Republican:

The picture of the new French Republican is conveyed chiefly by the character of M. Joseph Pagnol.

(i) The wish to cast off the defective moral values of the past

There was a feeling in France, that their defeat of 1870 by the Germans was punishment for moral excesses prevalent under the Empire of Louis Napoleon. In reaction, the predominant mood of these early years of the third Republic was serious and sober, which was also the temperament of M. Pagnol. When Marcel argues the case for living permanently at the holiday home, his father has to remind him that there is more to life than pleasures and he stresses the importance of hard work. Page 84

Tu as devant toi, reprit mon père, une année qui comptera dans ta vie : n’oublie pas qu’en juillet prochain, tu vas te présenter à l’examen des Bourses pour entrer au lycée au mois d’octobre suivant !(ii) The Republican faith in the role of education in improving society

The faith in education, expressed in the previous quotation, is typical of the optimistic mood of the new Republicans. Ignorance is the true enemy and education is the key to the brave new world. Marcel’s mother talks on a more practical level, telling Marcel that he will never achieve his ambition of becoming a millionaire, if he doesn't take his school exams. Marcel makes the amused comment that she had the firm opinion that wealth was a kind of school prize which infallibly rewarded hard work and education. Uncle Jules’ recommendation for education was, however, on a loftier level from his own experience of the intellectual satisfaction to be gained from reading the classics.

Joseph Pagnol is a constant advocate of education as a means of self-improvement. Following his declaration, quoted above, of the importance of Marcel’s forthcoming scholarship exam, he ensures that Marcel has the maximum support for his preparation pages 87 and 137.

He preaches the same message to Lili. As the Pagnol family say goodbye to Lili at the end of their summer holiday, M. Pagnol finds time for a short lecture to the little peasant boy about the value of education. Page 85

Au revoir, petit Lili. N’oublie pas que tu approches peu à peu de ton certificat d’études, et qu’un paysan instruit en vaut deux ou trois.(iii) The hard-working conscientious new Republican

Mr Pasquier applied his strict principles in his own life. He was hard-working and conscientious and a former pupil pays tribute to these attributes in his professional life. Bouzigue tells him that he owes his own successful career to all the effort M. Pasquier had put in to get him through his certificate examinations. It is out of his deep sense of gratitude that the canal superintendent insists on lending them a key so that they can take a shortcut to the holiday home page 110:

Je suis piqueur au canal, et c'est grâce à vous, je peux le dire: Vous vous en êtes donné du mal, pour mon certificat d'études(iv) The man of honesty and strict integrity.

Mr Pagnol Has a strong sense of personal integrity. He is amazed at his wife's ability to intrigue, when she deliberately gets into friendship with the headmaster’s wife, in order to win over the good lady and her husband to the desirability of Joseph having a free timetable each Monday morning - Page 109. Her husband, incredulous, asked for a full account of how she had done it and was scandalised:

Alors mon père ôta ses lunettes, les frotta vivement avec le bord de la nappe, et les remit sur son nez pour la regarder avec stupeur,…….Il fallut tout lui raconter par le menu….À la fin, il secoua la tête en silence plusieurs fois. Puis, devant toute la famille, il dit, avec une admiration scandalisée :

- Elle a le génie de l’Intrigue

M. Pagnol believed in abiding by the letter of the law. It took him many long days of heart searching before he could reconcile himself to flout official regulations by trespassing along the canal bank. Finally he could only do this by convincing himself he was rendering a useful service to the public, because he would be checking on the state of the canal’s cement lining and also because he came to accept Bouzigue’s assurance that his checks would be a help to him - Page 123

Il est évident dit enfin mon pire, que, si je puis rendre service à la communauté, même d'une façon un peu irrégulière …… et d’autre part si je puis t’aider.He prepared himself very conscientiously for this new responsibility. On the following Monday evening after school, Marcel’s father brought out 3 or 4 old books on canals – their cement and irrigation and began to study them. Only after long preparation was he able to see himself as an unofficial canal inspector and lead his family along the canal path with clear conscience, holding his maintenance notebook and his pencil in his hand. Page 124

Later in the book, Joseph Pagnol’s strict adherence to these principles placed him in a catastrophic situation. After the gamekeeper of the fourth château had caught them trespassing, he issued him with a legal summons. As a result, Marcel's father, knowing himself to be in the wrong, felt that he could not honourably continue in his teaching post and saw no other course than resignation. Mme Pagnol, who, as we have seen, was more flexible, told him that he was exaggerating their predicament. However, M. Pagnol, in deep depression was adamant. He was convinced that he would receive "un blâme" a reprimand from the Inspecteur d'Académie – the Chief Education Officer, which left him with no alternative.

il y a certainement de quoi infliger un blâme à un instituteur, Et pour moi, un blâme équivaut à la révocation, car je démissionneraiHis wife points out the extremity of this moral gesture, as he would also relinquish his pension – (Apparently, for the middle classes, a retirement pension was regarded as a brilliant promise for the future, offering a life of leisure, living off a private income.)

(v) His strict standards of sexual morality.

He disapproves of the immorality, which Bouzigue light-heartedly portrays in his tale of his sister's colourful life story page 167. Bouzigue’s metaphor for the need to take the chances that life offers was the crossing a raging torrent, by jumping from one rock to the next. . His sister had demonstrated this art and her case each rock was a lover more prosperous than the last. Enjoying the freedom of a husband who was away a lot of the time, her first rock been that of a tram depot manager. She had improved her condition in life by infidelity to her husband by jumping first to the rock of the tram depot manager, and had progressed to ever more illustrious rocks, until she now was landed on the rock of a town councilor. She was, in fact, thinking of jumping over to the rock of the head of the Prefecture.

Mme. Pagnol was not impressed and said disapprovingly that men must be stupid, but Bouzigue said his sister knew how to go about it. He added that intelligence wasn’t everything and that she was otherwise well endowed:

"L'intelligence, ce n'était pas tout" et qu’elle "avait un drôle de balcon".

When Paul and Marcel tried to peep at the photo Bouzigue produced of her fantastic figure, their mother sent them to bed.The views of M. Pagnol on this behavior were quite predictable in spite of his gratitude to Bouzigue. Late that evening, Marcel awoke from an incoherent dream of all this to hear his father complaining

"Tu me permettras de regretter qu'en ce monde, le vice soit trop souvent récompensé". During their meetings, Bouzigue constantly mentioned the strings he could pull by using his sister’s important lovers and we can imagine how the strait-laced Joseph must have winced.Although this is light hearted and amusing, it does remind us that the new Republic, working to establish a responsible and respected democracy, was discredited by well-known cases of official corruption and sexual scandal at the highest level.

(vi) His disapproval of over-indulgence in alcohol

As a matter of principle, Mr Pagnol was very abstemious. When socialising required him to share a drink, for example in the company of Bouzigue, he was careful to dilute the alcohol with Vichy water. He became very anxious when Uncle Jules produced a bottle of liqueur on his surprise arrival at their Christmas meal at la Bastide. He was very relieved when Jules reassured him that the bottle was non-alcoholic.

M. Pagnol regarded alcohol as a threat to health and was very worried about the harm he was doing, when he constantly refilled Bouzigue’s glass to celebrate their victory over the gamekeeper of the fourth château. Joseph was doubly anxious, because as they had had no wine in the house, he was pouring Bouzigue Pernod from the bottle that Mme Pagnol kept hidden in a bedroom wardrobe for the use of alcoholic visitors. He felt the absolute need to warn Bouzigue, but was afraid his words might make him sound mean –Page 166

Mon père hasarda, un peu timidement

- Je ne voudrais p[as que tu croies que je regrette cet alcool que tu vas boire. Mais je ne sais pas si, pour ta santé…To which, Bouzique replied that our fresh water tank was sure to contain dead spiders, lizards and toads for which Pernod was the perfect antidote –

"L'eau citerne, c'est de l'essence de pipi de crapaud ! Tandis que le pernod, ça neutralise tout!"M. Pagnol was particularly opposed to the abuse of alcohol because of its deleterious effects on the human character and thus on the quality of life. Page 136 -, The old colonel had told them the gamekeeper in the fourth château was an old, drunken degenerate and although Marcel’s father sought to play down the threat he posed, he totally deplored what alcohol could have done to the man.

- Le colonel nous a dit l’autre jour que c’était un vieil abruti.

- Abruti, très certainement puisque ce malheureux s’adonne à la boisson. Mais il est bien rare qu’un vieux pochard (boozer) soit méchant.The subsequent encounter of the Pagnols with this fearsome man gives a dramatic exhibition of the character degradation resulting from alcoholism.

Joseph Pagnol was by no means alone in regarding alcohol as a social evil. The growth of this problem was a major concern for European governments at the turn of the twentieth century. We may note that it was in 1904 that the eminent French statistician, Jacques Bertillon, published his comprehensive report: “L’Alcoolisme et les moyens de le combattre jugés par l’expérience.”

(d ) The view the book gives of the political sentiments the new Republicans

(i) Joseph Pagnol is hostile to the nobility.

In the traditional European order, derived from the Roman Empire, the King or Emperor and Church had exerted absolute power, with the nobility forming part of the ruling elite with absolute power over the common people. The French Revolution of 1789 had overturned this, dispossessing King, Church and nobility. After 1815, rule of King and then Emperor was restored and this lasted until the military defeat of the Emperor Napoleon III in 1870. This had allowed the French people a third attempt to set up a Republic.The aim of democracy of course was to empower the common people, but there were still many French people who longed for the certainties and the stability of the old order and monarchist and Bonapartist factions had significant support. To a committed French Republican therefore the nobility was the enemy.

Mr Pasquier shows a hostile reaction when he is told that the occupant of the first country house, whose grounds they pass through, is a nobleman. He says:

"Moi je n'aime pas beaucoup les nobles" – and Marcel immediately explains where his father had formed these ideas: Les leçons de l'école normale restaient ineffaçables".The “Écoles Normales” were state teacher training colleges, which traditionally were a hotbed of political radicalism. As a result of this education, Joseph had the conviction that in general the nobility was insolent and cruel and Marcel makes an ironical remark that the fact that many noblemen and women had had their heads cut off during the Great Revolution of 1789 only served to prove it-Page 115:

…d’une façon générale, il considérait “les nobles” comme des gens insolents et cruels, ce qui était prouvé par le fait qu’on leur avait coupé la tête. Les malheurs n’inspirent jamais confiance , et l’horreur des grands massacres enlaidit jusqu’aux victimes.However, when the Pagnol family met the nobleman who owned the first country house they found that he was neither insolent nor cruel. On the contrary, he was kindly and helpful and showed them the greatest courtesy, being especially attentive to Marcel's mother. He advised them to join the canal by coming through his front gate, then walking up his drive. It was the count's giant gamekeeper who used to carry the luggage of the Pasquier over the first stretch of the journey. Every week the nobleman arranged for Mme Pasquier to be presented with a bouquet of red roses and these are put in a vase in their home and kept all week. Marcel makes a comment about the irony of royal roses on display in their strongly republican home- page 132 :

…. notre maison républicaine était comme anoblie par les Roses du Roy.(ii) He is anti-clerical

The Catholic Church had been traditionally the twin pillar of authority along with the ruling Christian prince in the old order. During the nineteenth century, after the bitter experience of popular revolutions, the Vatican had regarded the new democratic movements establishing themselves across Europe, and the Popes had condemned them. In the contemporary French political arena, the monarchist and Bonapartist parties, mentioned above, that were campaigning to overturn the French government and the Republic could normally expect the support of the Church. As a result, most republicans, including M. Pagnol regarded the Church of Rome as their political enemy.

The Republicans were at variance with the Church also because of the prime importance which they gave to rationalism in their political philosophy. To many Republicans, the mysticism in the Church’s teaching and practices, on which the church based much of its authority was simply superstition. The conflict between mysticism or superstition and rationalism is presented amusingly at several points in the book and republican rationalism sometimes seems to have a shaky hold.

After Uncle Jules had told them, during their Christmas meal, that at Midnight Mass he had prayed to God that the family of Joseph Pagnol might be restored to the faith, Marcel went to bed very troubled. In accordance with the ideas of his father, Marcel knew that God did not exist, but he is not absolutely sure, because a lot of serious, intelligent people believed in God-page 104

Certes, je savais bien que Dieu n'existait pas, mais je n'en étais pas tout à fait sûr. Il y avait des tas de gens qui allaient â la messe, et même des gens très sérieux. L’oncle lui-même lui parlait souvent, et pourtant l’oncle n’était pas fou.Marcel is worried because, if there is a God, Jules might not have done them a favour by drawing God’s attention to them. He thinks of the case of a young man doing military service, whose father wrote to his Commanding Officer, an old friend, in the hope of making his life easier. In fact the C.O’s intervention revealed that the young man was on compassionate leave on the false pretext of his father’s and was living in the bedroom of the red-haired waitress of the neighbouring hotel. The request for higher intervention saw the young conscript thrown into a rat infested military dungeon. To calm his fears, Marcel finds an ingenious explanation for the co-existence of the two opposing beliefs: God, who didn’t exist for his family, certainly existed for other people, like the King of England, who only existed for the English.

Later in the story, Marcel again fails to show full confidence in his fathers’ rationalism. After running away from home during a winter night, Marcel had thought he saw a big dark figure go past them. Lili knew exactly who it was. It was the ghost of Big Felix, a shepherd of the olden times, who had been murdered by thieves and who came back looking for his lost treasure. Lili’s father had seen him four times and on his last visit had told the ghost that he hadn't got his money, and that if he didn't clear off he'd give him the signs of the cross and six kicks up the backside

"Moi, je respecte les morts, mais si tu continues comme ça moi je sors, et je te fous quatre signes de croix et six coups de pied au derrière".Marcel replies vehemently with the truths that his father had taught him : Page 75

Le fantôme, c'est l'imagination du peuple. Et les signes de croix c'est l'obscurantisme.However, Marcel is far from convinced and using some deviousness, he got Lili to show him how to cross himself.

As far as superstition was concerned, Joseph must have felt that his wife did not set a good example - One of the reasons why Augustine Pagnol was terrified of passing through the estate of the château that they had nicknamed the house of the Sleeping Beauty, was her belief that it was haunted.

These tensions are reflected within the Pagnol family, as Joseph’s closest friend, is his brother-in- law, Jules, who is a devout Catholic.

We find that other members of the household of Joseph Pagnol, failed to reach the rationalist certainties of the head of the family. After hearing the words of Uncle Jules, Marcel becomes anxious.

Conclusion

(a) This period of relative peace and tolerance

The years of the story, 1904-1905 lie in the period, to which was given in retrospect the title of “La Belle Époque”. It was a time when there was a new optimism that the advances in science and technology heralded a more prosperous future. The same mood was found in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain and in the United States, where the term the “gilded age” is sometimes used.

In France it was an era of relative peace, helped by a new spirit of tolerance. The movement towards social and religious change in sixteenth and seventeenth century Europe had led to mass slaughter of innocent citizens on a scale and with a savagery never surpassed in history. In the late eighteenth century, the reformers of the French Revolution had allowed their ideals to be swallowed up by the Terror. The Third Republic was bringing a radical change of government with no offence to civilised values.

In spite of one very black moment, the childhood years related by Marcel Pagnol form a kind of idyll. The happiness comes from a spirit of human love and tolerance. We can perhaps see this illustrated in the difference of opinion at Christmas between Joseph Pagnol and Uncle Jules.

While the Pagnol were enjoying their big meal in the early hours of Christmas Day, they had been delighted by the unexpected arrival of Uncle Jules, who had cycled all the way there. Jules explained that he had set off on this journey after attending midnight mass. He had gone to church alone because Aunt Rose had to stay at home with baby Pierre.

Uncle Jules described admiringly the festive decoration of the church and the carols they had sung. He then set Marcel’s father aback by announcing that he had prayed for him and his family at Church, that they might be granted faith.

After a moment’s unease, Joseph reminded his brother-in-law that he did not believe in the beneficent, personal Christian God. However, he recognised what he had done as a gesture of sincere friendship and thanked Jules.

"Je ne crois pas, vous le savez, que le Créateur de l'Univers daigne s'occuper des microbes que nous sommes, mais votre prière est une belle et bonne preuve de l'amitié que vous nous portez et je vous en remercie".At that moment, Marcel is aware that he has seen the wonder of true friendship Page 103:

Les enfants ne connaissent guère la vraie amitié. Ils n'ont que des « copains » ou des complices, et changent d'amis en changeant d'école, ou de classe, ou même de banc. Ce soir-là, ce soir de Noël, je ressentis une émotion nouvelle: la flamme du feu tressaillit, et je vis s'envoler, dans la fumée légère, un oiseau bleu à tête d'or.(b) The Belle Époque and its light hearted contrast with serious Republican ideals.

The emphasis in this review of history has been on seriousness of purpose the importance of application to the daily task, but that does not give the full picture. Bouzigue’s sister was not the only person who had fun in those days. This was the era of “La Belle Époque.

It is the world of Colette’s “Gigi” and for many people it is represented by the American musical film version in which Maurice Chevalier starred (see above). It was a time when the arts flourished. One peak event was the mass tribute that Paris gave to the poet Verlaine at his funeral in 1896. And Verlaine’s character and life contrasted totally with the Republican virtues of Joseph Pagnol listed above. He was irresponsible, idle, immoral, alcoholic, guilty of extreme violence, but the Parisians turned out in force, because he had graced their language with poems of great beauty.

The only glimpse of actual gaiety in “Le Château de ma mère” is in Marcel’s descriptions of the screams of the women of Marseille as they were swirled round at speed in the city’s fun park.

la féerie de Magic-City où j'étais monté sur les montagnes russes: j'imitais le roulement des roues de fonte sur les rails, les cris stridents des passagères, et Lili criait avec moi...More important than gaiety is the sense of happiness in the book, as Marcel tells the story of these years of his childhood in the secure affection of his parents and his brother and little sister. This happiness made possible by the spirit of the tolerance, which is necessary In the face of inevitable human differences. The strongly anti-clerical Joseph and the staunchly Catholic Jules are able to embrace each other warmly. Joseph, the lifelong foe of the aristocracy, has the red roses of a Count in his house all week.

(c) The dark aftermath – 1914- 1918/ 1939-1945

In the penultimate chapter of the book, five years have gone by and a sudden shock has destroyed Marcel’s happy family life. Marcel found himself walking, with his little brother Paul clenching his hand, behind the black hearse that was taking their mother away for ever - Page 168 :

"J'étais vêtu de noir, et la main du petit Paul serrait la mienne de toutes ses forces. On emportait notre mère pour toujours ».On this page two other personal tragedies for Marcel are listed. His younger brother Paul was to die in his early thirties. Lili was not at Paul’s funeral because he had died, shot through the head in the closing stages of the First World War.

Page 168- il était tombé sous la pluie, sur des touffes de plantes froides dont il ne savait pas les noms.The death of Lili links Marcel’s personal tragedy with the universal tragedy of world war. The sad end to his family idyll which we see at the end of the book, is reflected in history with the death of the optimistic hopes that had been nourished in the previous years and the pessimistc moral that Marcel attaches to his story seems equally true for the hopes of the people of the world at the start of the 20th century. Our brief ephemeral pleasures seem to be inevitably obliterated by time- page 168:

Telle est la vie des homes. Quelques joies, très vite effacées par des inoubliables chagrins.

Il n’est pas nécessaire de le dire aux enfants.In national politics this is matched by the famous words of the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, on the outbreak of World War One, which had in tow -though no-one, knew it then - the even greater horror of World War Two:

"The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our time”

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………POSTSCRIPT

Marcel Pagnol, who was a translator of William Shakespeare, would be aware of his principle not to end a piece of work on a note of pure negativism. The final chapter of “Le Château de ma mere” tells of a remarkable coincidence in his later life and also serves this purpose. Pagnol tells how, by a very remote chance thirty years later, he had bought unwittingly, the country house, where he had endured with his mother and family the most distressing episode of these years. Although it is a sad and emotional experience for the adult Marcel, there is perhaps, in this vivid reappearance of his family, the sense of human life having secret links and continuity.

END

(The following is the essay plan of the above Background Notes)

INTRODUCTION

a) The timespan of the book

b) The Geographical setting of the book

SECTION A -Aspects of country life in France at the start of the 20th CenturyA1) -The centuries old lifestyle

A2) -The character of the country peoplea) The peasants’ protectiveness of their lands

b) The independence of the peasantry

c) The superstitions of the peasantry

d) The kindness and helpfulness of the local people

e) The so-called « ignorance » of the peasantry.

f) Their status in contemporary society

SECTION B The general picture of French life at the start of the 20th Century

B1) –Aspects of their daily life

a) The pre- dawn of the great scientific revolution of the 20th century 1904- 1905

b) Changing transport options

c)The limitations of medical and scientific knowledge at this time.

- (i)Premature death

(ii) Phylloxera- d) Local colour

- (i) The picture of the traditional Christmas meal in Provence

- (ii) An amusing detail of contemporary habits - Queuing techniques in 1904

B2) – Aspects of French political life in the first decade of the twentieth century

a) A contemporary political figure to fix the date

b) The bitter memory of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870

c) The view the book gives of the new French Republican:

- (i) The wish to cast off the defective moral values of the past

- (ii) The Republican faith in the role of education in improving society

- (iii) The hard-working conscientious new Republican

- (iv)The man of honesty and strict integrity.

- (v) His strict standards of sexual morality.

- (vi)His disapproval of over-indulgence in alcohol

- d) The view the book gives of the political sentiments the new Republicans.

- (i) He is hostile to the nobility.

- (ii)He is anti-clerical

Conclusion

a) This period of relative peace and tolerance

b) The Belle Époque and its light hearted contrast with serious Republican ideals.

c) The dark aftermath – 1914- 1918/ 1939-1945